I loathe the phrase ‘publish or perish’.

As if we weren’t all under enough pressure, academics seem to relish adding life-and-death metaphors into the mix. Admittedly, ‘publish or perish’ serves to underline the importance of publishing in academia – and it is important – but this popular soundbite gives you no advice about how to go about it.

Towards the end of my PhD, I felt the pressure to publish mounting and mounting, but found limited advice about how to survive (let alone thrive) in this strange new and seemingly hostile environment. That’s where I hope this blog post might come in. The tidbits below stem from personal experience, but I hope they might prove helpful to others as they prepare to send their thesis and its insights into the big, bad world.

First, a tiny bit about me – I’m Jennie, I did my PhD from 2017-2020 and I’m now coming to the end of my first post-doc. I’m the proud author of two published journal articles based on my thesis, plus one that’s currently in press, and hopefully one to come out of a conference later this year. In the interest of balance, I should also point out that I’ve got another in article rehab after a pretty swift and summary rejection last Christmastime, and another that’s in the ‘I would love to write that when and if I ever have time’ pile/chasm/Mariana Trench. This blog post passes on some of what I’ve learnt while putting this happy band of papers together:

1) Less is more.

In my discipline (which I would roughly summarise as qualitative religious studies with a penchant for death and interdisciplinary work) a lot of people try and turn their thesis into a book. When I passed my viva, defending my beloved masterpiece against its oppressors (read: two very nice examiners), I considered going for the full monograph and living the dream of having my name on the side of a book, sharing my insights with the gushing public. But in the end, for reasons of time (and sanity), and at the advice of trusted colleagues, I opted instead to produce a small pool of strong, solo-authored articles in good journals.

I could submit work on different aspects of my thesis to a range of journals with diverse readership, rather than putting all the eggs in one book-shaped basket. This isn’t to say it’s necessarily any “easier” to write articles (more on that below) but for me it fit better around a full-time research contract. It’s not necessarily a case of trying to get every insight out there, either. I’d be happy if I wound up with three PhD-based articles, and delighted if it gets to four or five. The reward from fewer, better articles will likely be greater than from many articles which pack less of a punch. Check with others in your discipline to learn what worked for them.

2) It's not as simple as submitting a chapter.

I wish – and naively used to believe – that one could just lift a chapter from a thesis, submit it to an international journal, and have the editors immediately come back with an acceptance email having recognized your genius for what it is.

It’s… not quite like that.

That’s because PhD examiners and journal editors have different aims and expectations. A thesis is designed to prove you deserve a PhD, and your chapter is one of several building blocks towards your argument, whereas journal articles are designed to highlight original research contributions in a relatively short space to a readership which is often very specific. Those two goals overlap, but they aren’t identical.

My thesis chapter on vocation was original and took a fresh, critical angle; it was grounded in delicious, rich qualitative data and became one of the theoretical foundations of my arguments. But almost everything about its intended audience and its significance for a broader field of scholarship needed reconsidering and rewriting to get it published. I was proud of it as a thesis chapter and I’m actually even prouder of it now as a journal article. Expect to have to rework your ideas, not because they’re bad, but because they may well need to function differently for a journal audience.

3) It will require resilience.

I don’t remember crying about my PhD that much – but I’ve cried buckets over article rejections. I’ve had rejections that made me feel silly for even trying to submit to the journal, and reviews that have felt like knives slicing through words and arguments that I really believed in, and which really mattered to me – all the more because they were based on a thesis I worked hard on and I’m proud of. Those rejections aren’t always easy to take and knowing in advance that it might be painful lessens the blow. It means you can seek out support networks (mine is my Mum). I think my skin’s getting a little thicker with each submission. (This also means that when I’m asked to act as reviewer, I’m careful with my words and tone. You can suggest amendments without cutting something, or someone, to shreds.)

4) Reframe the feedback.

Building on that resilience, it’s important to try and see the value in what can look like a barrage of ‘things that you’ve done wrong.’ When my husband catches reviewers’ comments on my laptop screen over my shoulder, he’s usually horrified (and probably bracing to have to go and make consolation tea). I know how easy it is to see a wall of criticisms, full of comments that range from the bemused to the nit-picky, irrelevant, bizarre, and cutting. But while some reviewers are definitely kinder than others, I’m yet to find a reviewer who doesn’t offer something helpful.

I will be forever grateful to the anonymous soul who reviewed my article on vocation and saw its potential when I first submitted it, then stuck with it as I chipped away at their suggested revisions. So try not to believe all the memes about reviewer 2. They aren’t out to get you, and their comments might even contain the hook that takes your piece from ‘sound’ to ‘excellent.’

5) Find a mentor.

Being a solo-author doesn’t mean you should be trying to navigate publishing alone – especially at the beginning. I’ve been blessed with several wonderful colleagues on my research team at Aberdeen who are happy to help this fledgling researcher, who all really understand the pressure on ECRs (Early Career Researchers) to get their name and work out there. If you can find someone half as good as either of them, their mentoring will really help. Even if they aren’t from your discipline (mine aren’t) they’ll still have a wealth of publishing and writing knowledge and wisdom from which to draw. Mine have provided me with practical tips, emotional reassurance, lay explanations of the world of open access, and – perhaps most valuably of all – their own horror stories, to remind me that academic publishing can be tough for everyone, and it is definitely not just me.

6) Normalise the marathon.

One of my three publications was accepted by the first journal I sent it to after minor revisions.

Boom! Success! Lucky me!

But it wasn’t to be the pattern for all of them.

The second found its home in the second journal I sent it to, accepted, but subject to slightly more major revisions.

The third needed three journal submissions, and even then, the third journal required two hefty rounds of revise and resubmit.

It can take perseverance and graft to find the right home for your research. It also takes time – time writing, time researching journals, time formatting (my personal least favourite), and time responding to feedback, sometimes to then have to do all of that again. That’s normal, and I’ve learnt a lot from the process already.

7) Make a spreadsheet.

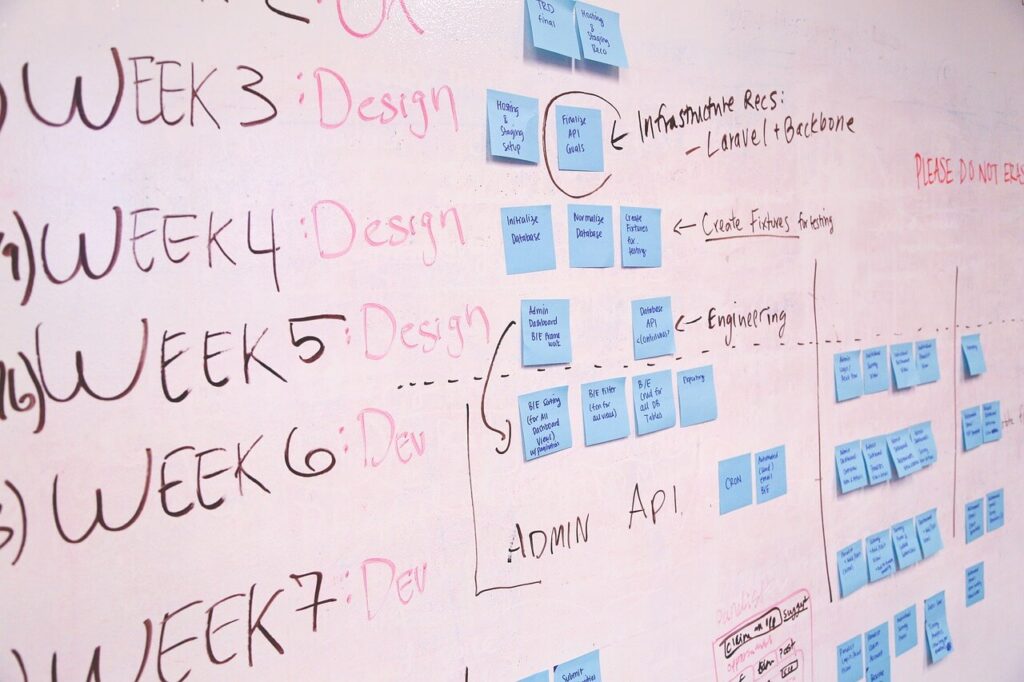

In fairness, I would apply this piece of advice to almost anything – and software other than Excel is available – a Word document or notes app, sticky notes on your desktop or even a good old fashioned piece of paper would achieve roughly the same outcome. The crucial thing is to compile relevant information.

For each article, I pop together a wee list of journals in the right fields, with links to their author instructions, their open access options, and key info like their preferred citation style and word or page counts. It means that if/when your first choice journal turns a manuscript down, you aren’t entirely back at the drawing board. I also find it helpful to use a spreadsheet to log my responses to reviewers’ comments, so that I can be sure I’ve addressed everything as best I can and can show the editors as much.

That’s my seven cents’ worth. I can only hope that if I rewrite this in five years’ time, I’ll have heaps of new things to include. But from one novice to another, I hope this article at least gives you some pointers on how to manage the weird world of academic publishing.